The Truth about Cholesterol and Heart Disease

[Part VII] ] Outlive by Peter Attia

Introduction

This post is going to be about Heart Disease, and because of the very detailed content available about it in the book, it needs more than one post to cover it well.

This is Part 1. It is based on chapter 7 of the book Outlive by Peter Attia.

This post covers the internal mechanisms that cause heart disease, but not what causes it, which will be covered in a future post.

Heart Disease: America's Deadliest Epidemic

Globally, heart disease and stroke (or cerebrovascular disease), which Peter lumps together under the single heading of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, or ASCVD, represent the leading cause of death, killing an estimated 2,300 people every day in the United States, according to the CDC—more than any other cause, including cancer.

It’s not just men who are at risk, American women are up to 10 times more likely to die from atherosclerotic disease than from breast cancer

Exact numbers: 1 in 3 vs 1 in 30.

But pink ribbons for breast cancer far outnumber the American Heart Association’s red ribbons for awareness of heart disease among women.

Heart disease is our deadliest killer, the worst of the Horsemen.

Peter believes that it need not be—that with the right strategy, and attention to the correct risk factors at the right time, it should be possible to eliminate much of the morbidity and mortality still associated with atherosclerotic cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease.

He thinks this should be the tenth leading cause of death, not the first.

The Truth about Cholesterol

Our heart and circulatory system are a marvel of engineering and physiology.

The heart relentlessly pumps blood throughout our bodies, delivering oxygen and nourishment to all our cells.

This complex yet efficient system keeps us alive and supports all functions of our bodies, yet runs automatically and non-stop.

It is almost perfectly designed to generate atherosclerotic disease, just in the course of daily living.

This is in large part because of another important function of our vasculature.

In addition to transporting oxygen and nutrients to our tissues and carrying away waste, our blood traffics cholesterol molecules between cells.

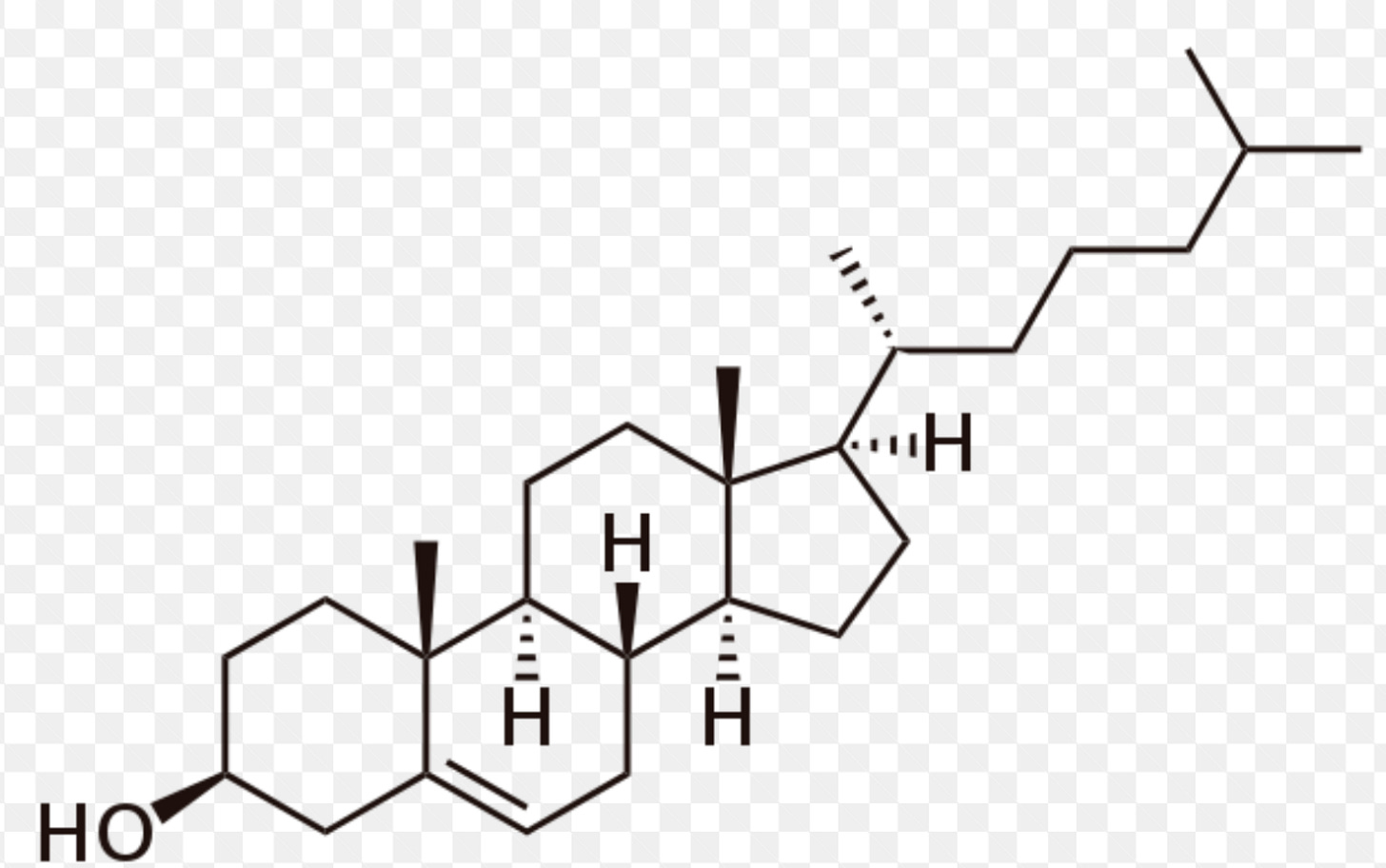

Cholesterol is essential to life.

It is required to produce some of the most important structures in the body, including cell membranes; hormones such as testosterone, progesterone, estrogen, and cortisol; and bile acids, which are necessary for digesting food.

All cells can synthesize their own cholesterol, but some 20% of our body’s (large) supply is found in the liver, which acts as a sort of cholesterol repository, shipping it out to cells that need it and receiving it back via circulation.

Structure of cholesterol, -OH alcohol group.

Because cholesterol belongs to the lipid family (that is, fats), it is not water-soluble and thus cannot dissolve in our plasma(blood).

So it must be carted around in tiny spherical particles called lipoproteins—which act like little cargo submarines.

These lipoproteins are part lipid (inside) and part protein (outside)

The protein is essentially the vessel that allows them to travel in our plasma while carrying their water-insoluble cargo of lipids, including cholesterol, triglycerides, and phospholipids, plus vitamins and other proteins that need to be distributed to our distant tissues.

The “Good” and the “Bad” Cholesterols

LDL (low-density lipoprotein) and HDL (high-density lipoprotein) are two types of lipoproteins that transport cholesterol and other lipids in the bloodstream.

LDL is often referred to as "bad cholesterol" because it carries cholesterol from the liver to the rest of the body, including the arterial walls.

HDL, on the other hand, is often referred to as "good cholesterol" because it helps to remove excess cholesterol from the bloodstream and transport it back to the liver for processing and elimination.

The reason they’re called high-and low-density lipoproteins (HDL and LDL, respectively) has to do with the amount of fat relative to protein that each one carries.

LDLs carry more lipids, while HDLs carry more protein in relation to fat, and are therefore denser.

Also, these particles (and other lipoproteins) frequently exchange cargo with one another.

If LDL becomes damaged or oxidized, it can be taken up by HDL and transported back to the liver for processing and elimination.

Additionally, HDL can transfer some of its apolipoproteins to LDL, which can help to improve the function and stability of the LDL particles.

When an HDL transfers its “good cholesterol” to an LDL particle, does that cholesterol suddenly become “bad”?

The answer is no—because it’s not the cholesterol per se that causes problems but the nature of the particle in which it’s transported.

Each lipoprotein particle is enwrapped by one or more large molecules, called apolipoproteins, that provide structure, stability, and most importantly solubility to the particle.

HDL particles are wrapped in a type of molecule called apolipoprotein A (or apoA), while LDL is encased in apolipoprotein B (or apoB).

This distinction may seem trivial, but it goes to the very root cause of atherosclerotic disease: every single lipoprotein that contributes to atherosclerosis—not only LDL but several others—carries this apoB protein signature.

Cholesterol from the diet doesn’t cause heart disease

Even Ancel Keys, the famed nutrition scientist who was one of the founding fathers of the notion that saturated fat causes heart disease, knew this was nonsense.

The problem he recognized was that much of the basic research into cholesterol and atherosclerosis had been conducted in rabbits, which have a unique ability to absorb cholesterol into their blood from their food and form atherosclerotic plaques from it; the mistake was to assume that humans also absorb dietary cholesterol as readily.

“There’s no connection whatsoever between cholesterol in food and cholesterol in the blood,” Keys said in a 1997 interview.

“None. And we’ve known that all along. Cholesterol in the diet doesn’t matter at all unless you happen to be a chicken or a rabbit.”

Heart disease doesn’t primarily strike old people

Another Myth: The notion that cardiovascular disease primarily strikes “old” people and that therefore we don’t need to worry much about prevention in patients who are in their twenties and thirties and forties.

50% of all major adverse cardiovascular events in men (and 33% in women), such as heart attack, stroke, or any procedure involving a stent or a graft, occur before the age of 65.

In men, 25% of all events occur before age fifty-four.

But while the events themselves may have seemed sudden, the problem was likely lurking for years.

Atherosclerosis is a slow-moving, sneaky disease.

Our risk of these “events” rises steeply in the second half of our lifespan, but some scientists believe the underlying processes are set into motion in late adolescence, even as early as our teens.

The risk builds throughout our lives, and the critical factor is time. Therefore it is critical that we understand how it develops, and progresses, so we can develop a strategy to try to slow or stop it.

The Path to Atherosclerosis

This isn’t a perfect analogy, but Peter thinks of atherosclerosis as kind of like the scene of a crime—breaking and entering, more or less.

Let’s say we have a street, which represents the blood vessel, and the street is lined with houses, representing the arterial wall.

The fence in front of each house is analogous to something called the endothelium, a delicate but critical layer of tissue that lines all our arteries and veins, as well as certain other tissues, such as the kidneys.

Composed of just a single layer of cells, the endothelium acts as a semipermeable barrier between the vessel lumen (i.e., the street, where the blood flows) and the arterial wall proper, controlling the passage of materials and nutrients and white blood cells into and out of the bloodstream.

It also helps maintain our electrolyte and fluid balance; endothelial problems can lead to edema and swelling.

Another very important job it does is to dilate and contract to allow increased or decreased blood flow, a process modulated by nitric oxide.

Last, the endothelium regulates blood-clotting mechanisms.

The street is very busy, with a constant flow of blood cells and lipoproteins and plasma, and everything else that our circulation carries, all brushing past the endothelium.

Inevitably, some of these cholesterol-bearing lipoprotein particles will penetrate the barrier, into an area called the subendothelial space—or in our analogy, the front porch.

Normally, this is fine, like guests stopping by for a visit. They enter, and then they leave.

This is what HDL particles generally do: particles tagged with apoA (HDL) can cross the endothelial barrier easily in both directions, in and out.

LDL particles and other particles with the apoB protein are far more prone to getting stuck inside because they are larger and more complex than HDL particles.

This is what actually makes HDL particles potentially “good” and LDL particles potentially “bad”—not the cholesterol, but the particles that carry it.

The trouble starts when LDL particles stick in the arterial wall and subsequently become oxidized, meaning the cholesterol (and phospholipid) molecules they contain come into contact with a highly reactive molecule known as a reactive oxygen species, or ROS(the cause of oxidative stress.)

Cholesterol and other lipids in LDL particles are more likely to be oxidized because they contain unsaturated fatty acid chains that are susceptible to oxidation.

Unsaturated fatty acids have double bonds between carbon atoms.

It’s the oxidation of the lipids on the LDL that kicks off the entire atherosclerotic cascade.

Now that it is lodged in the subendothelial space and oxidized, rendering it somewhat toxic, the LDL/apoB particle stops behaving like a polite guest, refusing to leave—and inviting its friends, other LDLs, to join the party.

The oxidized LDL particles provide a "nucleation site" for other molecules to attach to.

Many of these also are retained and oxidized. It is not an accident that the two biggest risk factors for heart disease, smoking, and high blood pressure, cause damage to the endothelium.

Smoking damages it chemically, while high blood pressure does so mechanically, but the end result is endothelial harm that, in turn, leads to greater retention of LDL.

As oxidized LDL accumulates, it causes still more damage to the endothelium.

The key factor here is exposure to apoB-tagged particles, over time. The more of these particles that you have in your circulation, not only LDL but VLDL and some others, the greater the risk that some of them will penetrate the endothelium and get stuck.

Going back to our street analogy, imagine that we have, say, one ton of cholesterol moving down the street, divided among four pickup trucks.

The chance of an accident is fairly small. But if that same total amount of cholesterol is being carried on five hundred of those little rental scooters that swarm around cities like Austin, we are going to have absolute mayhem on our hands.

So to gauge the true extent of your risk, we have to know how many of these apoB particles are circulating in your bloodstream.

That number is much more relevant than the total quantity of cholesterol that these particles are carrying.

In response to this incursion, the endothelium dials up the biochemical equivalent of 911, summoning specialized immune cells called monocytes to the scene to confront the intruders.

Monocytes are large white blood cells that enter the subendothelial space and transform into macrophages, larger and hungrier immune cells that are sometimes compared to Pac-Man.

The macrophage, whose name means “big eater,” swallows up the aggregated or oxidized LDL, trying to remove it from the artery wall.

But if it consumes too much cholesterol, then it blows up into a foam cell, so named because under a microscope it looks foamy or soapy.

When enough foam cells gather together, they form a “fatty streak”—literally a streak of fat.

Basically, this is the inflammatory response, during this process some enzymes are released which make the endothelium more vulnerable to damage, leading to more LDL particles sticking to it.

The fatty streak is a precursor of an atherosclerotic plaque, and if you are reading this and are older than fifteen or so, there is a good chance you already have some of these lurking in your arteries.

Yes, I mentioned “fifteen” and not “fifty”—this is a lifelong process and it starts very early.

The atherosclerotic process moves very slowly. This may be partly because of the action of HDLs.

If an HDL particle arrives at our crime scene, with foam cells and fatty streaks, it can suck the cholesterol back out of the macrophages in a process called delipidation.

It then slips back across the endothelial layer and into the bloodstream, to deliver the excess cholesterol back to the liver and other tissues (including fat cells and hormone-producing glands) for reuse.

Its role in this process of “cholesterol efflux” is one reason why HDL is considered “good,” but it does more than that.

Newer research suggests that HDL has multiple other atheroprotective functions that include helping maintain the integrity of the endothelium, lowering inflammation, and neutralizing or stopping the oxidation of LDL, like a kind of arterial antioxidant.

The role of HDL is far less well understood than that of LDL.

The cholesterol content in your LDL particles, your “bad” cholesterol number (technically expressed as LDL-C), is actually a decent if imperfect proxy for its biological impact; lots of studies have shown a strong correlation between LDL-C and event risk.

But the all-important “good cholesterol” number on your blood test, your HDL-C, doesn’t actually tell very much if anything about your overall risk profile.

Risk does seem to decline as HDL-C rises to around the 80th percentile.

But simply raising HDL cholesterol concentrations by brute force, with specialized drugs, has not been shown to reduce cardiovascular risk at all.

The key seems to be to increase the functionality of the particles—but as yet we have no way to do that (or measure it).

If we are to make any further progress in attacking cardiovascular disease with drugs, we must start by better understanding HDL and hopefully figuring out how to enhance its function.

Back at the crime scene, the ever-growing number of foam cells begin to sort of ooze together into a mass of lipids, like the liquefying contents of a pile of trash bags that have been dumped on the front lawn.

This is what becomes the core of our atherosclerotic plaque.

And this is the point where breaking and entering tilts over into full-scale looting.

In an attempt to control the damage, the “smooth muscle” cells in the artery wall then migrate to this toxic waste site and secrete a kind of matrix in an attempt to build a kind of barrier around it, like a scar.

This matrix ends up as the fibrous cap on your brand-new arterial plaque.

More bad news: None of what’s gone on so far is easily detectable in the various tests we typically use to assess cardiovascular risk in patients.

We might expect to see evidence of inflammation, such as elevated levels of C-reactive protein(CRP), a popular (but poor) proxy of arterial inflammation.

The inflammatory response in atherosclerosis at this stage is not strong enough to produce significant increases in CRP levels.

But it’s still mostly flying below our medical radar.

If you look at the coronary arteries with a CT scan at this very early stage, you will likely miss this if you’re looking only for calcium buildup.

You have a better chance of spotting this level of damage if using a more advanced type of CT scan, called a CT angiogram, which I much prefer to a garden-variety calcium scan because it can also identify the noncalcified or “soft” plaque that precedes calcification.

A CT angiogram is a type of medical imaging that uses contrast dye to visualize the blood vessels in the body.

This type of CT scan can detect the presence of non-calcified or "soft" plaque, which can be a precursor to calcified plaque formation.

At a certain point in this process, the plaque may start to become calcified. This is what (finally) shows up on a regular calcium scan.

Calcification is merely another way in which the body is trying to repair the damage, by stabilizing the plaque to protect the all-important arteries.

A positive calcium score is really telling us that there are almost certainly other plaques around that may or may not be stabilized (calcified).

If the plaque ruptures, it can expose the blood to the inner lining of the artery. (As the plaque is on top of endothelium)

This can trigger a series of events that lead to clot formation.

Clots can block arteries and prevent blood from flowing to the heart or brain. This can lead to a heart attack or stroke - which is basically when heart muscles don’t get blood!

This is why we worry more about the noncalcified plaques than the calcified ones.

Fifteen years ago, the apoB test (simply, measuring the concentration of apoB-tagged particles) was not commonly done.

Since then, evidence has piled up pointing to apoB as far more predictive of cardiovascular disease than simply LDL-C, the standard “bad cholesterol” measure.

According to an analysis published in JAMA Cardiology in 2021, each standard-deviation increase in apoB raises the risk of myocardial infarction by 38% in patients without a history of cardiac events or a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease (i.e., primary prevention).

That’s a powerful correlation.

Yet even now, the American Heart Association guidelines still favor LDL-C testing instead of apoB.

We are fortunate that many of these conditions can be modulated or nearly eliminated—including apoB, by the way—via lifestyle changes and medications. Get apoB as low as possible, as early as possible.

I will be discussing these changes in future posts!